Isotope tests ID salmon remains at Interior Alaska site

August 29, 2016

Jeff Richardson

907-474-6284

Ice age inhabitants of Interior Alaska relied more heavily on salmon and freshwater fish in their diets than previously thought, according to a newly published study.

A team of researchers from –‘”˚…Á made the discovery after taking samples from 17 prehistoric hearths along the Tanana River, then analyzed stable isotopes and lipid residues to identify fish remains at multiple locations. The results offer a more complex picture of Alaska‚Äôs ice age residents, who were previously thought to have a diet dominated by terrestrial mammals such as mammoths, bison and elk.

The project also found the earliest evidence of human use of anadromous salmon in the Americas, dating back at least 11,800 years.

The results of the study were published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DNA analysis of chum salmon bones from the same site on the Tanana River had previously confirmed that fish were part of the local indigenous diet as far back as 11,500 years ago. But fragile fish bones rarely survive for scientists to analyze, so the team used sophisticated geochemistry analyses to estimate the amount of salmon, freshwater and terrestrial resources ancient people ate.

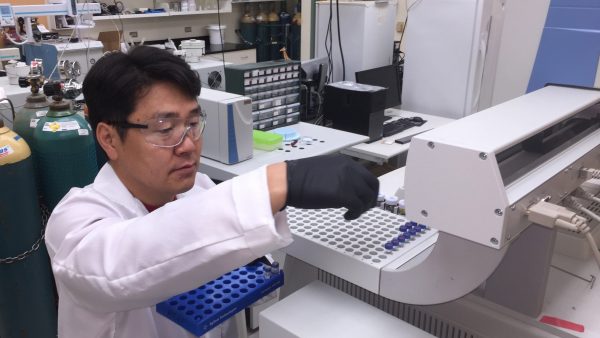

A team led by –‘”˚…Á postdoctoral researcher Kyungcheol Choy analyzed stable isotopes and lipid residues, searching for signatures specific to anadromous fish. The effort demonstrated that dietary practices of hunter-gatherers could be recorded at sites where animal remains hadn‚Äôt been preserved.

“It’s quite new in the archaeology field,” Choy said. “There’s a lot in these mixtures that’s hard to detect in other ways.”

Ben Potter, a professor of anthropology at –‘”˚…Á and co-author of the study, said the findings suggest a more systematic use of salmon than DNA testing alone could confirm.

“This is a different kind of strategy,” Potter said. “It fleshes out our understanding of these people in a way that we didn’t have before.”

The study required cooperation between –‘”˚…Á‚Äôs Department of Anthropology and the Institute of Northern Engineering‚Äôs Alaska Stable Isotope Facility to locate and interpret the presence of salmon remains at the sites. Potter said the process could be a template for how a diverse team of researchers can work together to overcome a scientific obstacle.

“It’s an awesome look at how we can merge disciplines to answer a question,” he said.

Other participants in the study included –‘”˚…Á researchers Matthew Wooller, Holly McKinney, Joshua Reuther and Shiway Wang.

ADDITIONAL CONTACTS: Kyungcheol Choy, 907-474-1585, kchoy@alaska.edu; Ben Potter, bapotter@alaska.edu, 907-474-7567; Matthew Wooller, 907-474-6738, mjwooller@alaska.edu