Tritt-Frank helps teach a village the value of education

April 26, 2017

Leona Long

907-474-5086

With an upside-down box for a desk and her 11 siblings dutifully sitting in a row as her students, Caroline Tritt-Frank was a teacher decades before she formally took that role at her village’s one-room school house.

She had always loved school and preferred reading to doing housework. Maybe that was why the years she spent juggling University of Alaska Fairbanks correspondence classes with raising her two daughters in a traditional subsistence lifestyle never seemed particularly overwhelming. In 1990, Tritt-Frank became the first person to graduate from college in Vashraii K’oo (Arctic Village), a remote Alaska Native community of about 175 people where Gwich’in have lived for thousands of years.

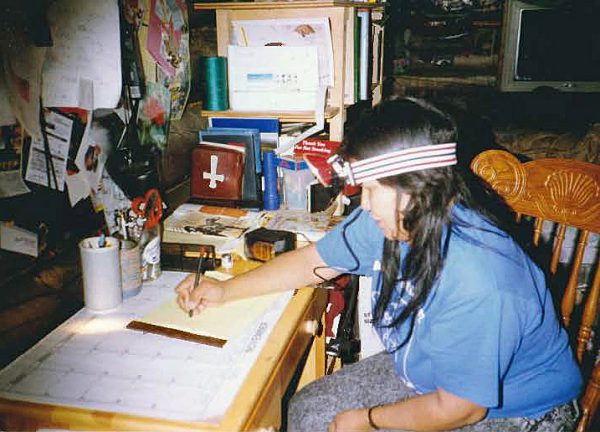

As her two little girls played quietly at her feet, Tritt-Frank squinted to make out the words in her textbook. Even with two Coleman lanterns and the kerosene lamp on her desk, there wasn’t enough light in their one-room log cabin for her to read. That’s when her husband, Kenneth Frank, had a bright idea. Without saying a word, he left and returned with a headlamp so Tritt-Frank would have enough light to read and write her assignments on a yellow legal pad.

Online classes weren’t an option when Tritt-Frank was earning her bachelor’s degree in education in the late 1980s. Instead, she took correspondence classes where professors mailed her lessons and assignments. Handing in homework meant either walking a mile each way to the post office or sending a fax one page at a time.

“It was faster to walk to the post office and back than wait for the fax machine,” said Tritt-Frank, who still has her homework stashed away in her family’s cabin back in Arctic Village. “I waited for what sometimes seemed like an eternity for my professors to mail back my graded papers.”

After graduating from –‘”˚…Á in 1990, Tritt-Frank was promoted from a teacher‚Äôs aide to the teacher at the Arctic Village School, where she had worked since 1972. As a Gwich‚Äôin immersion teacher, she taught all classes in science, reading and social studies in her indigenous language. While it was impossible to translate all of the curriculum into Gwich‚Äôin, she used the language to make academics more meaningful and relevant to her students.

"I became a teacher because I don't want to lose my language,” said Tritt-Frank, who was part of the painstaking effort to translate voting and election materials from English into Alaska Native languages like Gwich’in. The November 2016 election was the first time that her 91-year-old mother, Naomi, who speaks very little English, could understand the ballot.

When Tritt-Frank walked across the stage at her commencement, she didn‚Äôt know she was starting a movement. Her example inspired those around to her realize that they could make their dreams of a college education a reality. Her husband, daughters and best friend, as well as more than a dozen of her former students, followed in her footsteps by earning degrees from –‘”˚…Á. A decade later, Frank-Tritt walked across the stage again, this time to receive her master‚Äôs degree in education.

Caroline‚Äôs daughter, Crystal Frank, hadn‚Äôt started kindergarten when she first accompanied her mom to meet with an academic advisor at –‘”˚…Á‚Äôs Interior Alaska Campus. She remembers playing hide-and-seek with her sister in the Harper Building. It was those visits, and watching her mom study by the light of the headlamp every night, that made Crystal decide that when she grew up she was going to college too.

‚ÄúWhenever I felt discouraged in school, I thought of my mom,‚Äù said Frank, who is a graduate student and administrative coordinator for –‘”˚…Á‚Äôs Center for Cross-Cultural Studies. ‚ÄúShe knew that earning a degree from –‘”˚…Á would make our lives better. She made it through college without luxuries like a computer, running water or electricity and while raising two little girls. Even though it was challenging for her because English is her second language, she never complained or talked about giving up. Her example motivated me to earn my master‚Äôs degree from –‘”˚…Á too.‚Äù

When Tritt-Frank was 16, she was sent away to Mt. Edgecumbe High School, a boarding school at Sitka in Southeast Alaska. During that era, the late 1960s, boarding schools forbade Alaska Native students from speaking their traditional languages. Even though she knew she would be punished, Tritt-Frank remained steadfast in her commitment to keep her culture and language alive. She persevered because even at a young age, she knew she wanted her children to speak their language and live their culture. Today, she, her daughters and Kenneth, who also attended boarding school, are among several hundred fluent Gwich’in speakers and language learners.

Once as punishment for speaking Gwich’in language in class, Tritt-Frank and three of her cousins were not allowed to join their classmates at weekly movie night.

“We pushed barrels next to the windows and watched the movie anyway,” said Tritt-Frank. “It was a Western movie. It didn’t matter to us that we couldn’t hear. We didn’t speak English well enough to understand what the actors were saying."

Such punishments didn't stop her from speaking her indigenous tongue.

"Gwich’in is the language of my soul and worthy of that sacrifice," she said.